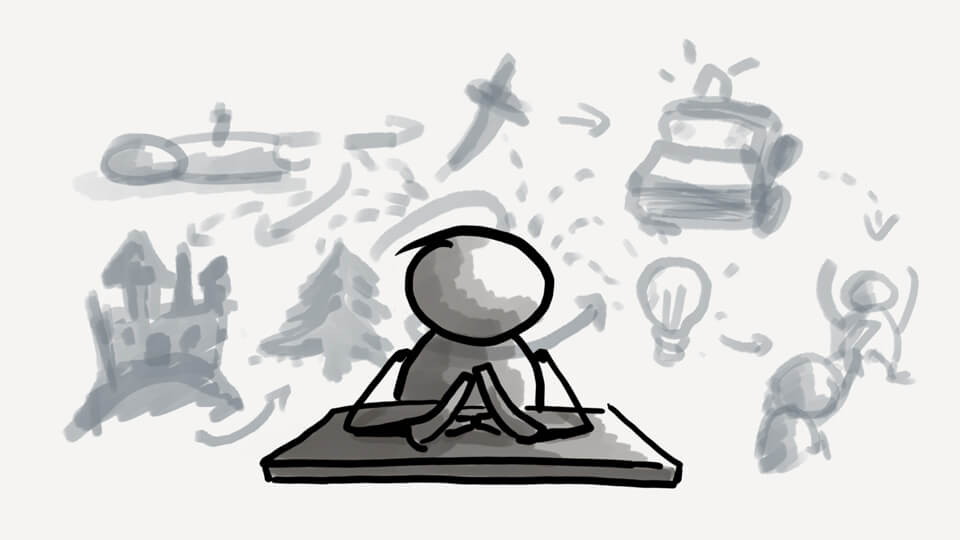

All great stories happen to the backdrop of a rich backstory. But how to give the readers the necessary context and nuanced layers of meaning without boring them? The answer is: subtly.

The goal of any backstory is to find its way into your narrative without your readers feeling overwhelmed, or being served the infamous info dump. I’ll show you how to sneak any amount of backstory you like in a way that will not only avoid boring your readers but will pull them even deeper into the setting you created.

I know not all genres are equally susceptible to boring their readers with long and unnecessary explanations (fantasy and sci-fi are the most notorious because of all the world building that needs to happen on their pages), but no matter the genre you write in, you should be able to pick up a trick or two from this post.

Why Readers Hate Backstories?

Because backstories are boring. Readers enjoy a narrative that flows and a writer that gets straight to the point. Like I just did now.

When NOT to Introduce the Backstory

1. Early on. Imagine picking up a book. It’s a fantasy novel by an author you haven’t read before. It opens with an intriguing hook. But then, when things should be getting more interesting, the author goes into a two-page-long explanation a magic system that you absolutely have to understand before being able to comprehend what happens next. The author drones about ancient symbols, and legs, and… Thud. You snap the book shut, and put it back on the bookstore shelf.

“But why,” I can almost hear the moaning author in my head, “why did they put the book down before they got to the interesting bits?”

Because you bored them.

Respect your readers’ time. We all have so little of it these days.

2. Chapter two. “Alright. They got this far. Now’s the time for that backstory I’ve cut from chapter one.”

Chapter two has traditionally been the place where most authors hid their backstory. Many still do, and they get away with it because if the readers cared enough about the story to reach chapter two, they should be able to tolerate a couple of boring paragraphs in order to fully appreciate the work the author has done.

Don’t mistake this kind-spirited tolerance for enjoyment. Many of your readers are likely to skim over the backstory and skip to the next sequence of events or the nearest piece of dialogue.

Don’t tell me you’ve never done it.

3. The middle of action and drama. Nothing interrupts a juicy scene like a sudden and unsolicited info dump.

If you think it’s crucial for the reader to understand that Josh is really the son of Frank, not Trevor, and his elder sister is really his mother who had him at a very young age and that the birthmark on his hand actually came from his mothers attempt to dispose of him when he was an infant, then you have a really messed up imagination, but you’re also absolutely forbidden from dumping all that information on the reader during a single scene.

4. Chapters three to ninety-nine. Now we covered chapters one, two, and— in case you’re wondering— any prologues, let’s extend our info dumping ban to cover all the remaining chapters of your book.

You managed to start off strong, why stop at all?

I know what you might be thinking now: “Alright, you cheeky bastard. How on earth am I going to introduce my backstory, then?”

Character Relationships

Foreshadowing is our biggest ally when it comes to introducing a backstory.

Let’s go back to that messed up family example. If our hero has a different biological father than the one he calls dad, the last thing we want to do is one mighty reveal. We’re not Sherlock Holmes, explaining our impeccable logic to Dr. Watson (the reader).

We can do much better.

We should pepper the narrative with all sorts of hints that suggest Frank plays an unusually involved role in our hero’s life. He takes him on trips, showers him with gifts for Christmas, always shows up to get him out of trouble, and generally shows a great deal of care and attention. Like a father would.

If we left a proper trail of breadcrumbs, then, when the big reveal finally arrives, it will all suddenly make sense to the reader, and leave them feeling more satisfied with the story.

And you just told a complex backstory through how characters interacted.

Dialogue Implications

You can use a similar technique when telling backstory through dialogue. A simple “Yeah, and what do you know about being a father?” uttered in anger by the hero, can send the reader’s mind flying in search of more.

As long as you leave the backstory implied rather than explicit.

Oh, and be careful of what the industry calls the “Two Talking Bobs.” That’s where two characters have a conversation explaining some part of the backstory or worldbuilding only to the benefit of the reader.

The Ways of the World

In the effort to spice things up, writers sometimes describe their genre with flavor. Like cyberpunk or dark fantasy, but then skip the kind of writing that would make their futuristic setting actually punk, or a fantasy world dark, grim, and perilous.

Dark Fantasy doesn’t mean all the lights went out. It means that this world is a pretty dangerous place, especially for people crazy enough to be heroes.

World building through careful storytelling means that instead of simply walking through dirty, and beggar-filled alley, like the omniscient cameraman, the heroes will actually get mugged.

Dark fantasy doesn’t mean that everyone dresses in stylish black leathers, and carries ornate daggers. It means a random drunken cutthroat will stab your hero with a rusted shiv during a bar fight.

Now, say an important part of your backstory is a war that happened recently. The world is still recovering from it. Instead of writing a couple of paragraphs explaining what had happened in this world of yours you could have:

- Widows and orphans everywhere.

- Rampant crime, because the government can’t control the situation yet.

- Damaged characters who have all lost someone they loved.

- Lots of crippled people everywhere. Wounded soldiers that wish they had died in that war of yours.

- People getting worked up when the war gets mentioned in a conversation.

Such details, squeezed into your narrative, can tell a much more powerful backstory than any paragraph-long summary. Your readers will feel, rather than be told, that the world is recovering after some great war.

You might not even need to use the word “war” once.

Little Details

Let’s talk some fluff. Old posters. Torn newspaper. Rectangles of clear wallpaper on a faded wall. An expensive but mismatched set of clothes. These can all tell great stories.

Imagine a half-faded poster, trampled into the mud, of an astronaut asking for volunteers for the first Mars colony. Such item tells a much better backstory than a whole chapter devoted to how humanity tried and failed to colonize the red planet.

Pick any kind of everyday object, and use it to suggest the presence of a rich and nuanced story of the world your characters inhabit.

On my recent trip to London, I saw a homeless man, covered in blankets in a fort made out of cardboard. His face was lit by the blue light of his mobile phone and the Facebook feed he was scrolling through.

What would that tell a reader about our world or the man’s story?

Fractal Storytelling

All of the mentioned techniques boil down to this: Telling stories is like exploring a fractal. The closer you look, the more details the fractal can reveal.

When we write, we spend a lot of time getting to understand our characters and setting, and where things came from.

The truth is, our readers don’t care for all that detail. A snippet from page seven of the newspaper the hero is reading makes the whole newspaper real, even if it doesn’t have a front page.

About a month ago, I was reading a sci-fi fantasy novel and I remember sometimes skipping a paragraph or two and sometimes a whole page until I got to the nearest dialogue. Its backstory was interesting but told in an uninteresting way. Now I know what mistakes to avoid. Thanks Sebastian.

Samwell, I’m glad you found this helpful.

I had a similar experience too many times to count and it made me think what makes the reader want to fast forward. Especially since the reader who wants to fast forward cares enough about the story and characters that he wants to fast forward and find out what happens next.

Yeah, exactly